- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

The Theorem that Won the War: Part 1 – Enigma on Paper

|

In 1923, the firm of German engineer Arthur Scherbius (1878–1929) began selling a machine that could encrypt messages automatically. Marketed as Enigma, it was soon adopted (and adapted) by the German military, and by the outbreak of World War II, it was used for almost all important German military communications. To understand the mathematics behind Enigma, it helps to have an Enigma machine. Unfortunately, most of the remaining machines are in museums, whose curators don’t take too kindly to handling their exhibits, so we’ll have to make do with a mockup. Online Enigma emulators are available, but to understand the mathematical details, we’ll set up a simple “paper” Enigma to analyze key points. We will do this in two parts, pausing to take part in some specific activities along the way. |

Figure 3. Enigma machine in use in a radio tank during the Battle of France in May 1940. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0 de.

|

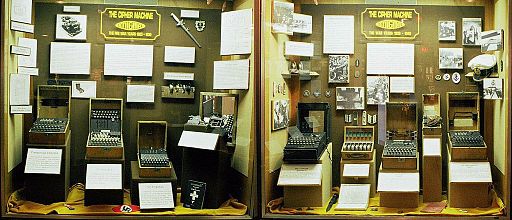

Figure 4. A display of Enigma machines and paraphernalia exhibited at the U.S. National Cryptologic Museum.

Left side of display: Enigma machines from 1923 to 1939. Right side of display: Enigma machines from 1939 to 1945.

Photographs by Robert Malmgren. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

Jeff Suzuki (Brooklyn College), "The Theorem that Won the War: Part 1 – Enigma on Paper," Convergence (October 2023)