- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

Teaching Mathematics with Ephemera: Primary Source Analysis of Ephemera

A piece of ephemera can consist of an image, a short body of text, or a mix of image(s) and text. Thus, the techniques of historical analysis to utilize depend on what the item actually is. A drawing or photograph must be "read" visually, describing what is depicted and attempting to determine what the illustration meant to its creator and its viewers. A detailed list of each component of the image is needed in order to determine which particulars are most significant. If possible, it is helpful to ascertain the materials used to create the image. With written sources, researchers use the words of the document to identify its author's main points and to infer the author's point of view. Ephemera with a blend of images and text require a combination of the techniques for visual and written materials. In both cases, of course, those studying the source must record who made it, when, where, for whom, and for what purpose. Similarly, elaborating on historical context is vitally important to the analysis of any primary source. Further, whenever possible, primary sources should be compared to other primary sources to test the validity of the interpretations developed by researchers—do they hold up when applied to additional historical evidence? Students can also use the conclusions reached by the authors of scholarly secondary sources to corroborate their ideas. Educators at the National Archives have shared worksheets for primary source analysis that are aimed at K–12 students (NARA, 2018). While training undergraduate history majors, the author has adapted the form in (Drake and Brown, 2003) to making sense of written documents and visual sources or physical objects. See also John Lee's suggestions for classroom activities with ephemera (Lee, 2018).

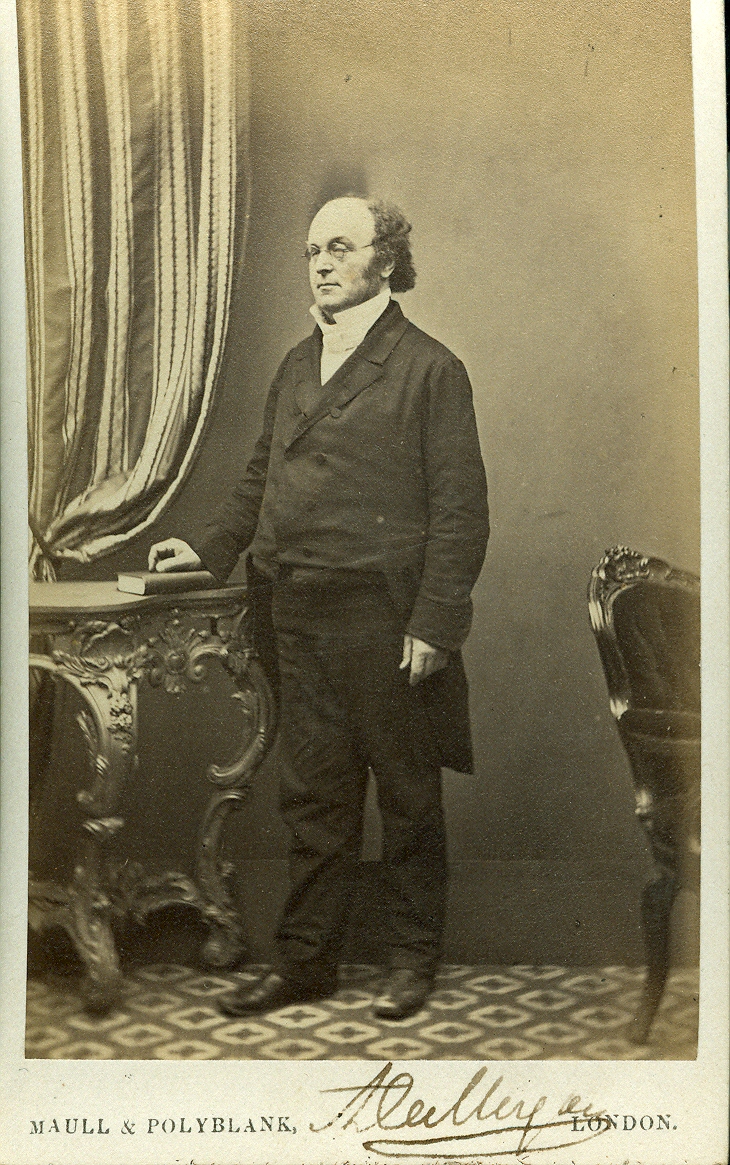

Carte de visite (visiting card) of Augustus De Morgan, signed "ADeMorgan", circa 1866.

From the collection of Dr. Sid Kolpas.

For instance, we can perform a quick analysis of Augustus De Morgan's visiting card, whose image appears in the Mathematical Treasures section of Convergence. The webpage supplies an approximate date and the information that the signature is in De Morgan's own hand. Professor Sid Kolpas also points out that the portrait was taken by the London studio of Maull & Polyblank for inclusion in a book of forty photographs and biographies of "celebrities". This reason for creating the image may explain why De Morgan's pose is formal and the furniture and setting convey the sterility of a professional business rather than, say, the informality and comfort of De Morgan's own study. Unfortunately, the dimensions of the card are not provided, but when the other information given is combined with some reading about the etiquette of calling cards in Victorian England, it appears likely that De Morgan would not have used copies of this card for his run-of-the-mill socializing. Men's cards were typically plain, with just their names and possibly their address. They were used to announce a gentleman's availability to conduct a social call that had been requested by the lady of the house; the lady could decide to receive him at that time or instruct him to return later (Cronin and Rogers, 2003; Hoppe, 2000; "Victorian Calling Card Etiquette"). They were not intended as permanent keepsakes. As an exercise for the reader, why, then, might De Morgan have wanted to distribute copies of his portrait?

Amy Ackerberg-Hastings (Independent Scholar), "Teaching Mathematics with Ephemera: Primary Source Analysis of Ephemera," Convergence (April 2019)