- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

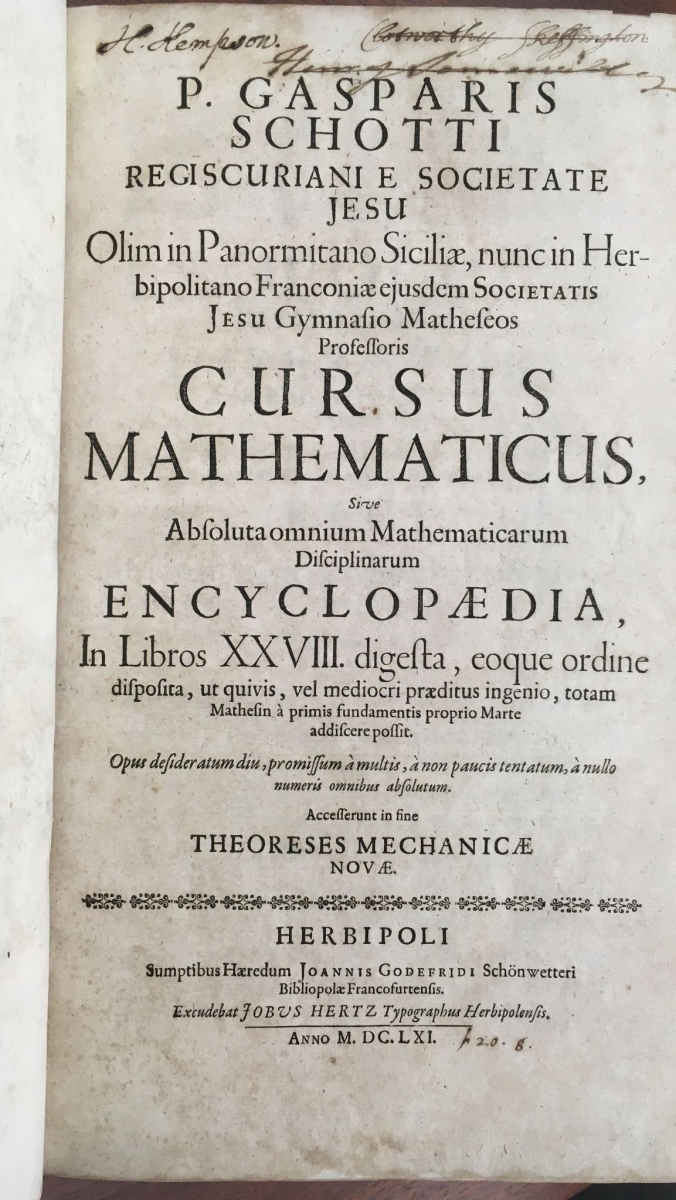

Mathematical Treasure: Gaspar Schott's Cursus Mathematicus

Born in Könighafen, Germany, Gaspar Schott (1608–1666) began his Jesuit training in 1627 at Würzburg University, where he studied philosophy and mathematics under Athanasius Kircher for two years. After completing his studies, he taught and ministered for 19 years in Sicily until he became Kircher’s assistant in Rome. After his transfer back to Germany, Schott found patrons to fund the publication of his books and corresponded with many scientists of his time. He became known as a teacher, author, and disseminator of scientific knowledge.

His mathematical encyclopedia, Cursus Mathematicus sive absoluta omnium mathematicarum disciplinarum encyclopædia (1661), containing 28 books (that is, chapters), greatly improved on the existing mathematical encyclopedias [Knobloch 2011]. The title page claims that even students with “mediocre talents can independently learn the whole of mathematics” [Knobloch 2011, p. 228].

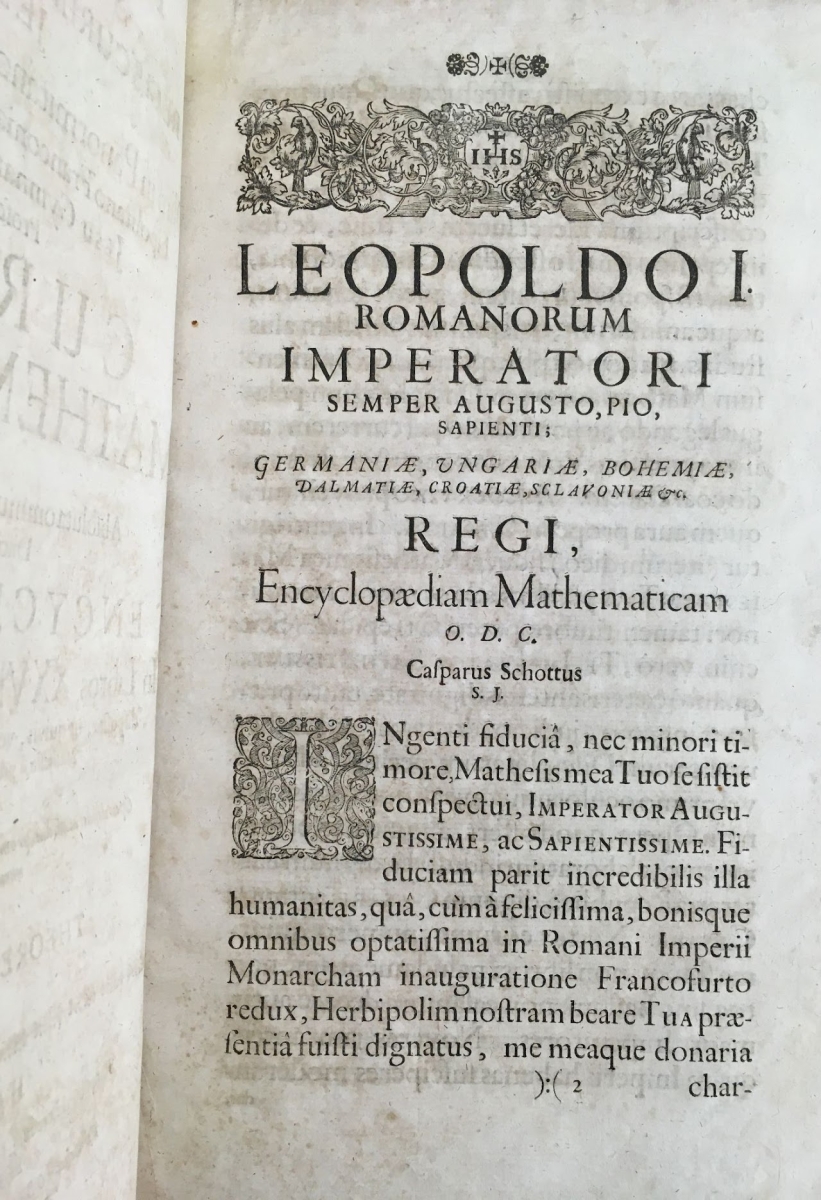

Schott’s homage to Emperor Leopold in the dedication is continued in the frontispiece, along with a preview of some of book’s contents. Each mathematical floor-tile corresponds to a book in the encyclopedia. For example, the lower left tile, containing a completing-the-square diagram, represents the book on algebra. The tile next to it, showing a proof of the Pythagorean Theorem, stands for the book on Euclid’s Elements.

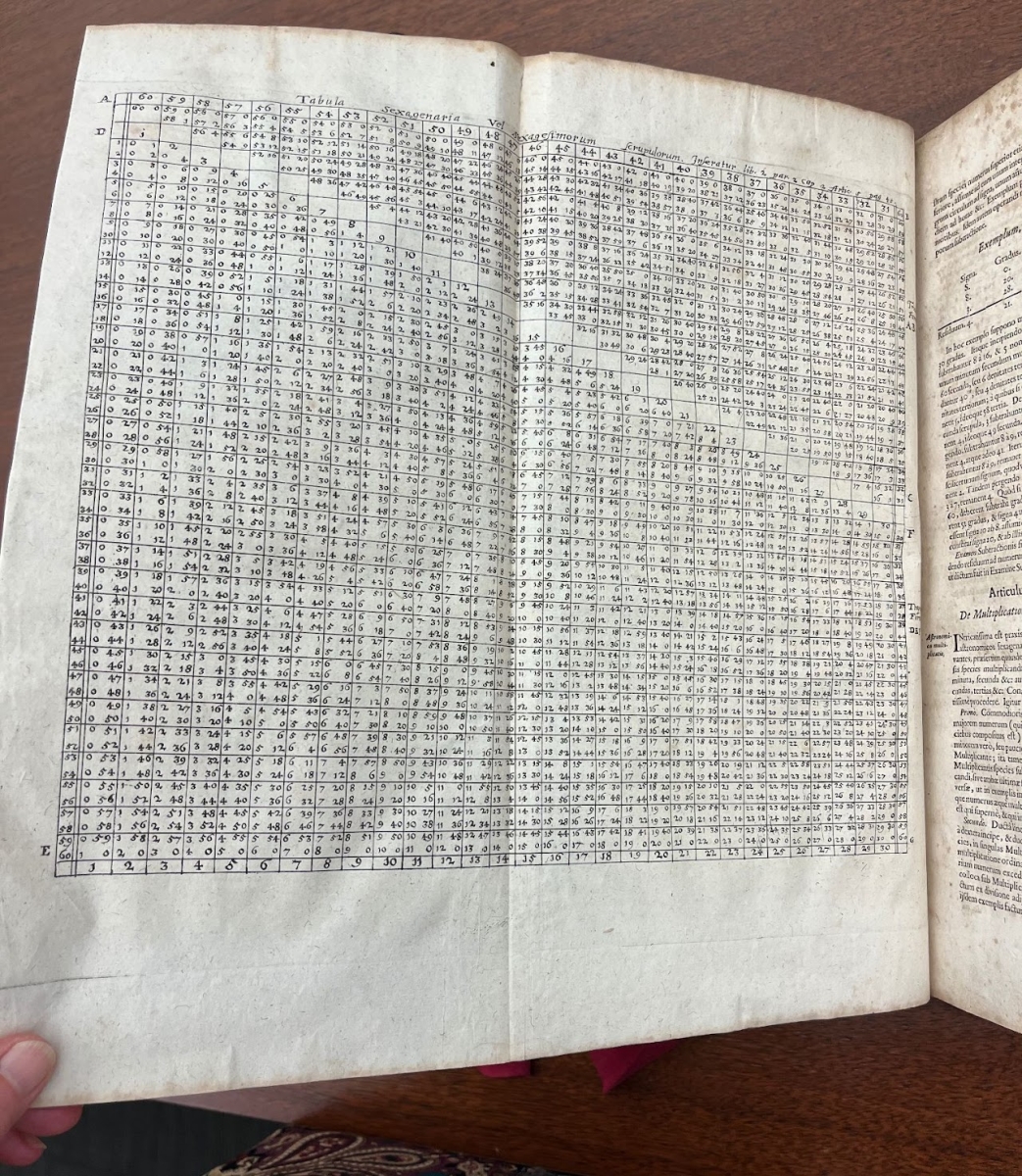

The practical arithmetic book has this fold-out table showing multiplication in base 60, used in astronomy. For 38x50, one finds the sexagesimal answer “31, 40” below 38 in row A and opposite 50 in the rightmost column. (To confirm, one would divide 38x50 by 60 to obtain 31 remainder 40.)

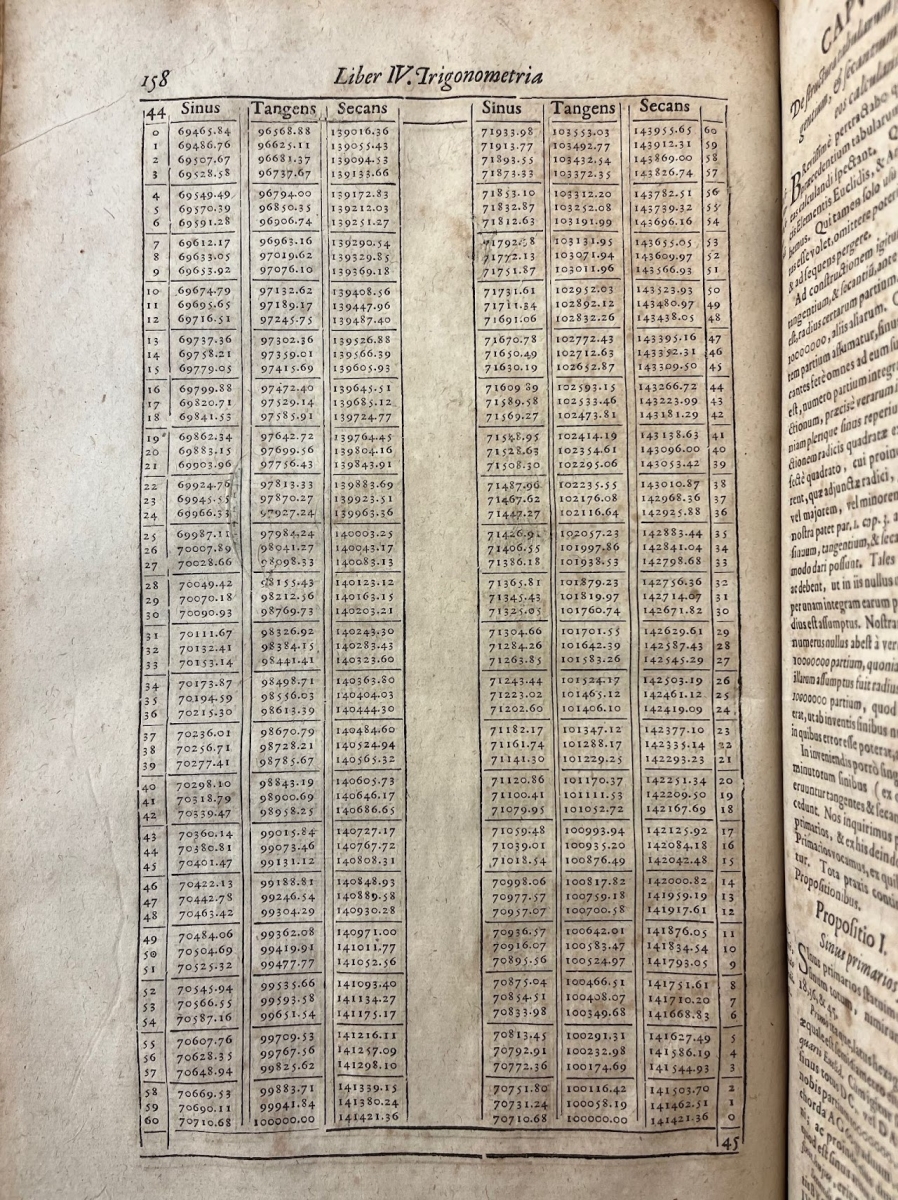

The trigonometry book gives sine, tangent, and secant approximations for angles 0° to 90°. The page shown has values for 44° to 46° (which, as Schott explains, must be divided by 100,000).

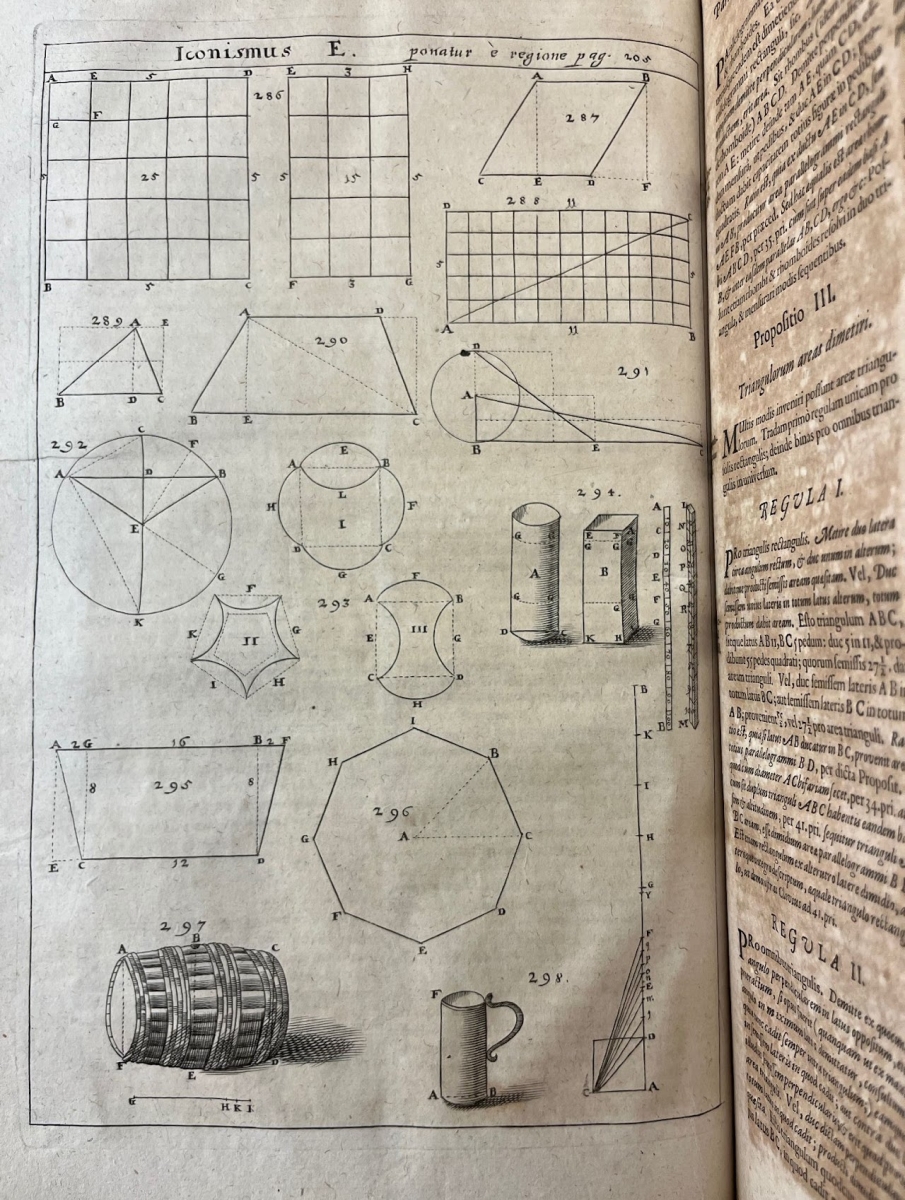

The practical geometry book contains the following three pages. This page shows areas and volumes, which are computed in the text.

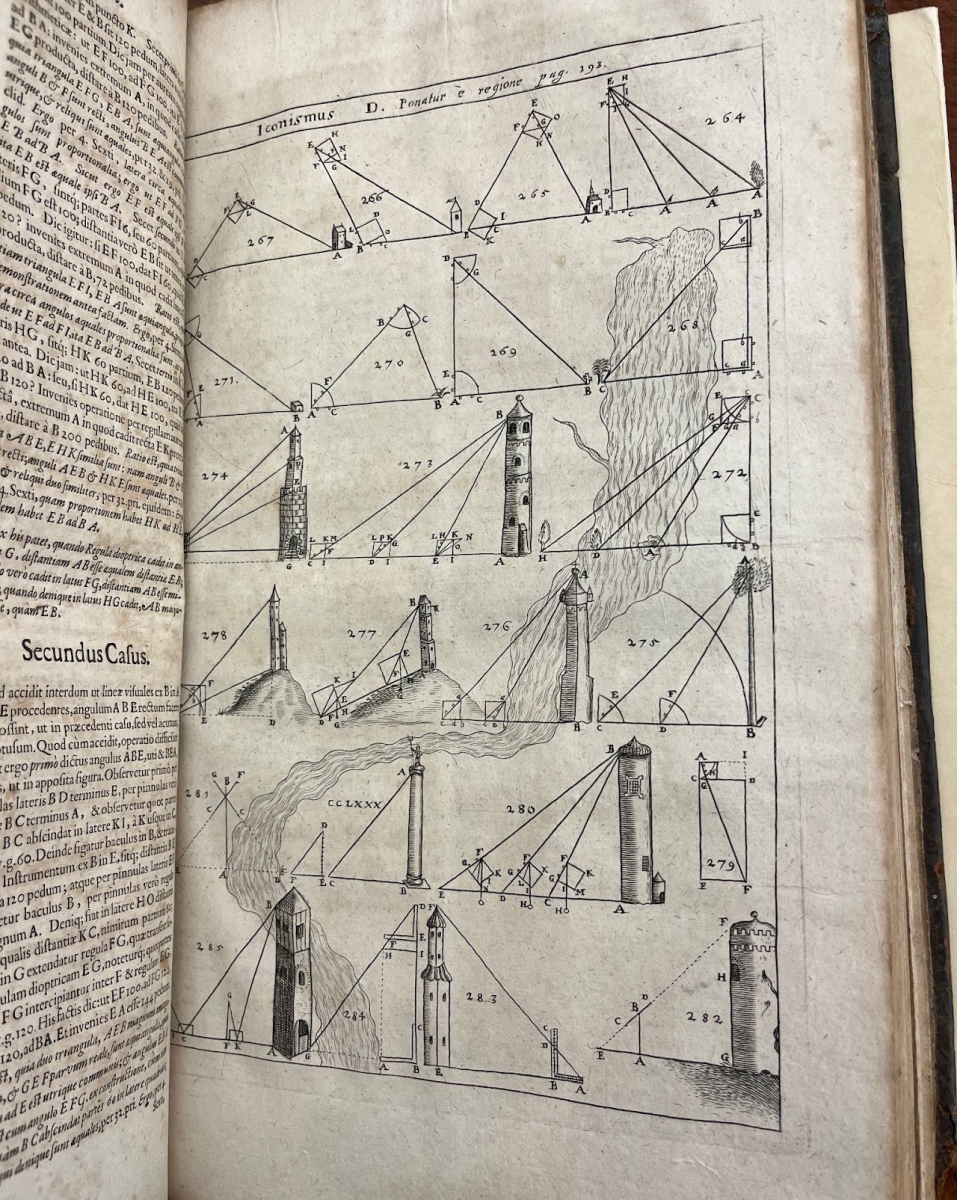

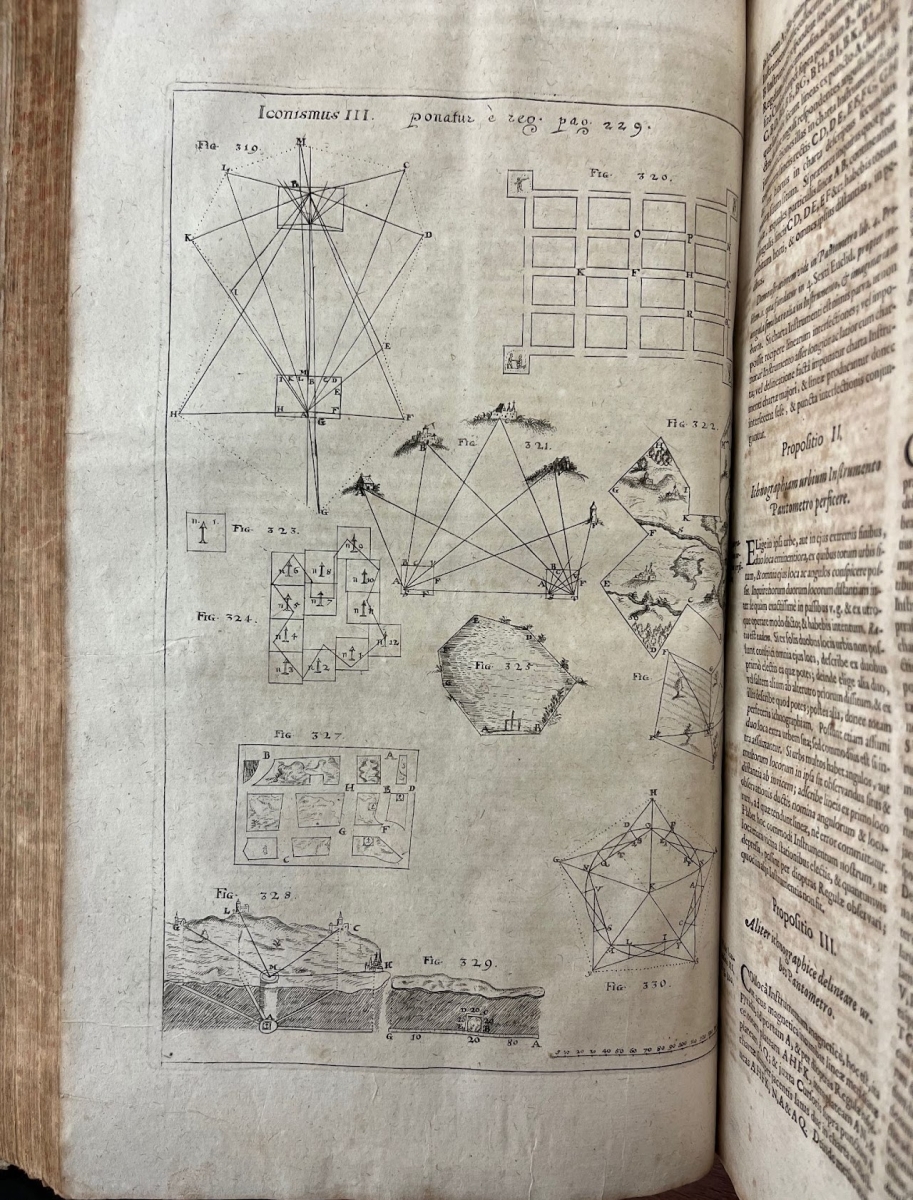

This page relates to range finding and calculating the heights of towers, and the image below it illustrates digging subterranean tunnels and other military applications.

All of the images on this page are provided courtesy of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, Loyola Marymount University [SPEC COLL QA33 .S35 1661]. The photos were taken by Jacqueline Dewar. A full digitization of the book is available through the Munich Digitization Center MDZ at https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/details:bsb11199830.

References

Brock, Henry M. 1913. Gaspar Schott. Catholic Encyclopedia.

Conlon, Thomas E., and Hans-Joachim Vollrath. n.d. The Correspondence of Caspar Schott. Early Modern Letters Online.

Conlon, Thomas E., and Hans-Joachim Vollrath. n.d. Transcriptions and Translations of the Correspondence of Caspar Schott. Early Modern Letters Online.

Findlen, Paula, ed. 2004. Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. New York: Routledge.

Keller, A. G. 2008. Schott, Gaspar. In Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, edited by Charles C. Gillespie, xii: 210–211. Rev. ed., New York: Charles Scribner.

Hellyer, Marcus. 2005. Catholic Physics: Jesuit Natural Philosophy in Early Modern Germany. Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press.

Knobloch, Eberhard. 2011. Kaspar Schott’s “encyclopedia of all mathematical sciences.” Poiesis & Praxis 7: 225–247. DOI: 10.1007/s10202-011-0090-1.

Udías, Agustín. 2015. Jesuit Contribution to Science: A History. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Cynthia Becht, Head of the Department of Archives and Special Collections at the William H. Hannon Library, for her encouragement and assistance as they prepared this article.

Jacqueline M Dewar (Loyola Marymount University) and Sarah J Greenwald (Appalachian State University), "Mathematical Treasure: Gaspar Schott's Cursus Mathematicus," Convergence (August 2024)