- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests: Classroom Slide Rules – Rules for Student Use

Most slide rule manufacturers (and there were at least 800 of them [Keane 2008]) made products for a range of audiences:

- General-purpose rules for working professional, with scales capable of calculating arithmetic operations, logarithms, square and cube roots, exponents, trigonometric functions, and vectors.

- Special-purpose rules designed for specific occupations, such as radio engineers, meteorologists, or statisticians.

- Rules with a limited set of scales to train high school and undergraduate students, apprentices, and others in the process of masting computing techniques.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of models of slide rules were thus designated for student use between about 1890 and 1970. Companies like K&E vigorously advertised their student slide rules, highlighting especially the lower prices that were made possible by both fewer scales—which reduced a firm’s development time and the complexity of engraving—and, probably more significantly, cheaper materials such as cardboard and plastic. These less expensive rules were more consumable and less likely to survive for long periods of time, but so many millions of them were made that plenty can still be found in thrift stores or estate sales as well as in museum collections.

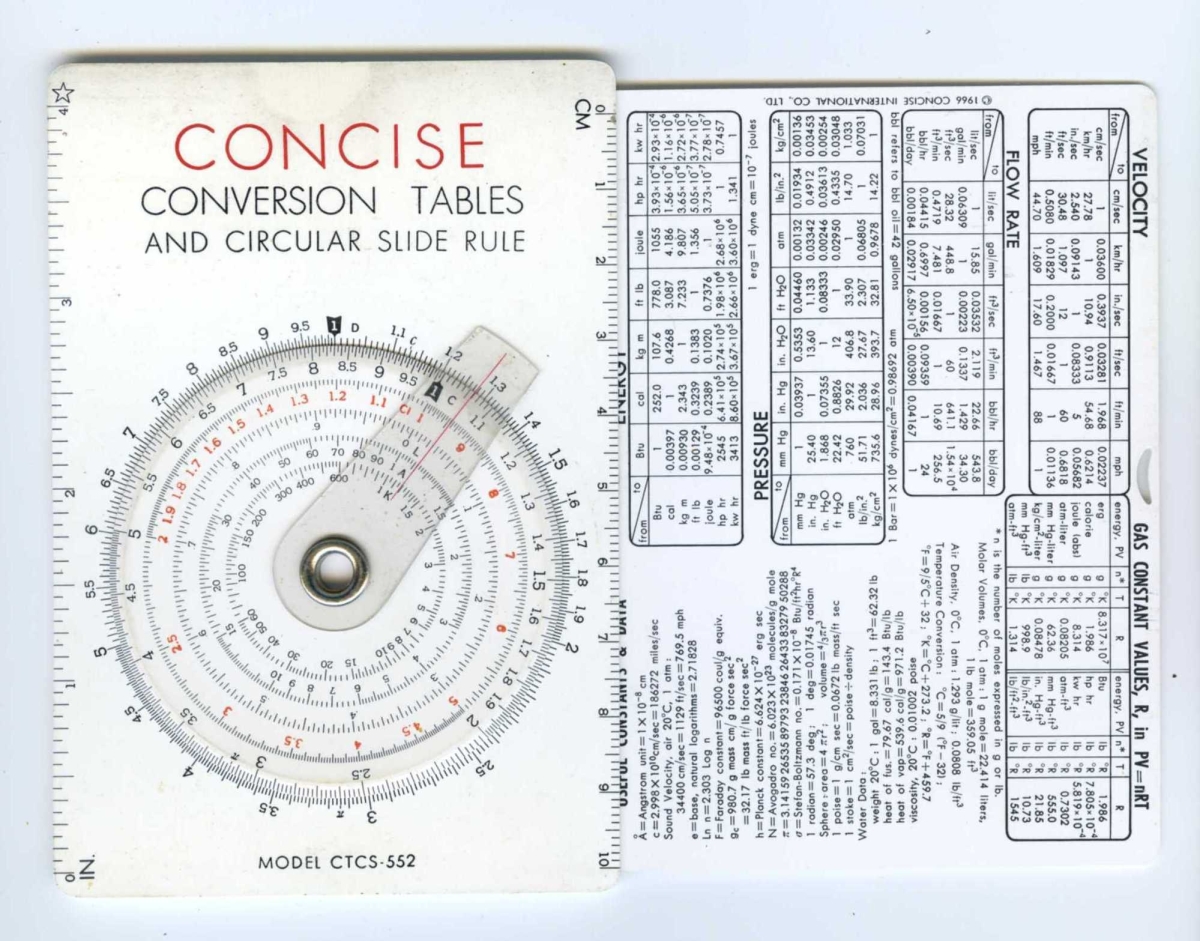

Figure 6. Although this article has focused on linear slide rules, the circular slide rule shown above was designed by students for students. It could carry out multiplication and division, determine logarithmic values, and compute squares, cubes, square roots, and cubic roots. It was distributed after 1966 by a Japanese company as model CTCS-552 under the US brand name Concise. Smithsonian Institution negative number NMAH-AHB2009q09077.

Even though student slide rules were far more ubiquitous than demonstration slide rules, most searches on the keywords “student slide rules” again yield few results. A search on the phrase “student slide rule” using the link at the top of the home page for the International Slide Rule Museum brings up 72 objects to explore. The Oughtred Society’s Archive of Collections also comes through with a number of examples. Some other options:

Even though student slide rules were far more ubiquitous than demonstration slide rules, most searches on the keywords “student slide rules” again yield few results. A search on the phrase “student slide rule” using the link at the top of the home page for the International Slide Rule Museum brings up 72 objects to explore. The Oughtred Society’s Archive of Collections also comes through with a number of examples. Some other options:

- The Smithsonian’s Collections Search Center returns two rules and three sets of instructions, which could be used to supply manufacturers and models for additional searches.

- Harvard University’s Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments displays two objects.

- Two objects from the Computer History Center may be viewed.

- The MIT Museum has two objects so labeled, although only one has been photographed.

- The Science Museum Group provides 5 records, but only one contains an image.

One way to do further research is to collect model numbers for one or more manufacturers or retailers and then search the internet for those model numbers. Clark McCoy’s scanned pages from K&E Catalogs and Price Lists offer an excellent starting point; K&E’s occasional Educational Products Catalogs are especially helpful.

One way to do further research is to collect model numbers for one or more manufacturers or retailers and then search the internet for those model numbers. Clark McCoy’s scanned pages from K&E Catalogs and Price Lists offer an excellent starting point; K&E’s occasional Educational Products Catalogs are especially helpful.

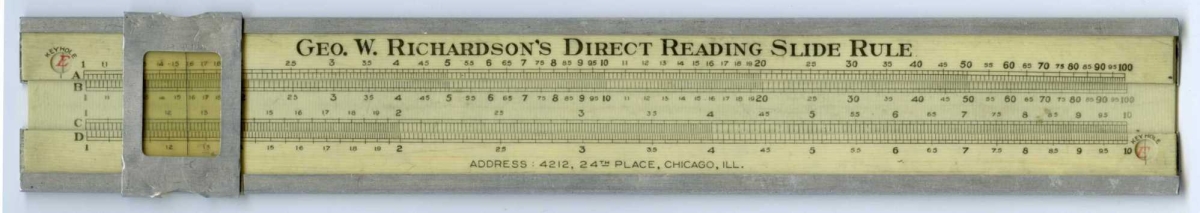

Figure 7. Richardson Direct Reading Slide Rule, ca 1909. George Washington Richardson (ca 1866–1940) was an individual American maker who tried to make inexpensive, basic slide rules that were affordable for students and blue-collar workers. Smithsonian Institution negative number NMAH-AHB2009q09170.

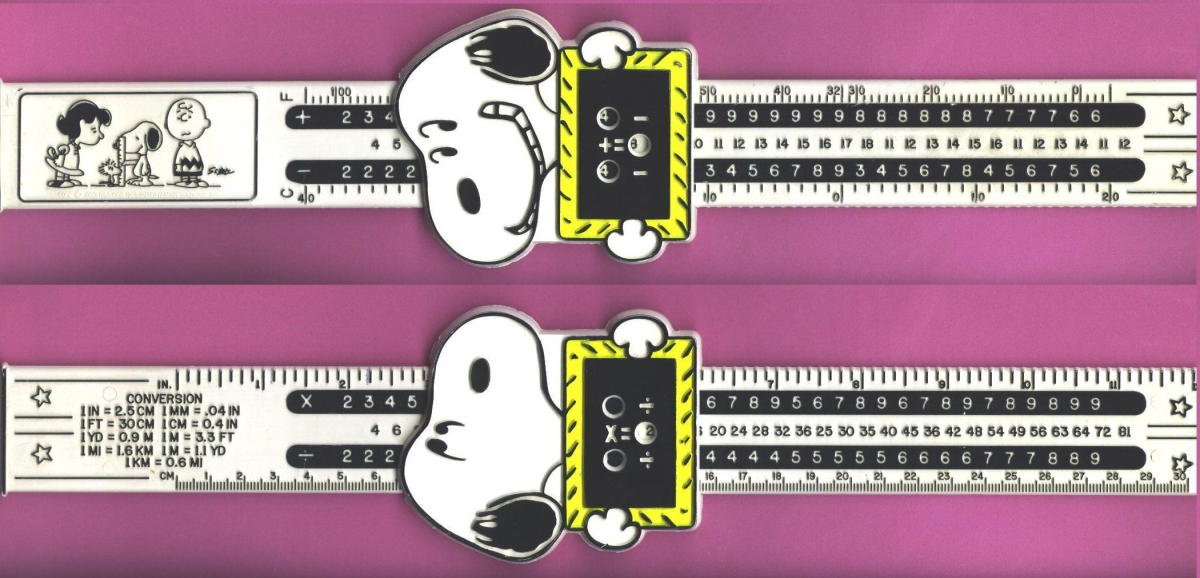

Early in the 20th century, American college professors and administrators made a concerted effort to outsource instruction in the slide rule to high schools, so that freshmen could move directly into the technical work of mathematics, engineering, and physics [Kidwell, Ackerberg-Hastings, and Roberts 2008, pp. 117–122]. Indeed, as late as the 1970s, popular cartoons were licensed to intrigue small children with the possibility of STEM careers—my parents gave me one of the Snoopy “slide rules” shown in Figure 8 when I was in elementary school. Today, both secondary schoolteachers and undergraduate professors provide enrichment activities based on slide rules. The instruments make excellent manipulatives for math circles, too. Some links to help readers get started can be found on the next page.

Figure 8. Snoopy Slide Rule, 1960s–1970s. International Slide Rule Museum.

Amy Ackerberg-Hastings (MAA Convergence, "Keys to Mathematical Treasure Chests: Classroom Slide Rules – Rules for Student Use," Convergence (September 2023)