- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

“A Magazine of all perfection”: Mathematics in the Early Modern Satire Histrio-Mastix – The Mathematical Muses

In addition to the human characters in the play, the so-called mathematical muses (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy) also play central roles. In fact, in Early Modern engravings such as frontispieces, these visual representations of various mathematical sciences were not strictly muses but rather personifications equipped with attributes that identified them. They also offered the potential for symbolic communication, for instance when arithmetic and geometry were each portrayed as wings that supported all of mathematics [Remmert 2009; Swetz 2020]. Additionally, frontispieces often presented visualisations of the structure, grandeur, and utility of the mathematical sciences.

Figure 7. Urania, the muse of astronomy, is supported by her wings,

geometry and arithmetic [Remmert 2009]. Detail from Isaac Brun (1596–1669),

“Eigentliche Fürbildung Vnd Beschreibung Deß Kunstreichen Astronomischen

vnd Weitberümbten vhrwerks zu Straßburg im Münster” (Broadside, 1621). British Museum

Collections Online 1880,0710.321. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

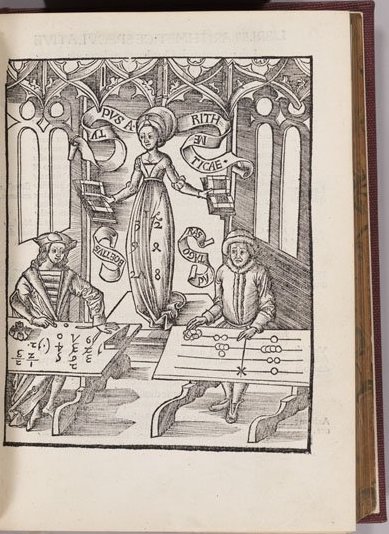

Chief among the subjects were the ‘purest’ ones, arithmetic and geometry, whose muses were depicted with standard attributes. For geometry, the ruler and compass were frequent allusions to Euclid’s works, and these drawing instruments were often shown in connection with shapes such as triangles or circles, or even with important constructions and diagrams. Similarly, for arithmetic, her attributes were—as would be expected—usually numbers, but often strewn about, and not always in the form of the Hindu-Arabic numerals in common use today: Not only were there other number systems around (primarily Roman numerals), but even when they were shown, Hindu-Arabic numerals looked markedly different from their modern versions [Swetz 2014]. In several important cases, the Early Modern transition from Roman arithmetic to the Arabic system was shown by a juxtaposition of an old reckoning board with handwritten symbolic computations [Swetz and Katz 2008].

Figure 8. The personification of Arithmetic, judging between the new Hindu-Arabic numerals

and arithmetic and the old ways of reckoning. Arithmetic clearly wears the attributes of numbers and

favours the new practices. In his 1503 book, Margarita Philosophia, Gregor Reisch (1467–1525)

actually taught both methods. Convergence Mathematical Treasures.

When reading plays such as Histrio-Mastix, it is evident that the Ancient and Medieval personifications of arithmetic and geometry as muses served as handy identifiers for the dramas’ Early Modern audiences, both to represent the concrete disciplines which they embodied, but also—qua muses—to stand for a set of pure, rigorous, and even transcendent qualities that these mathematical sciences were understood to exhibit. For example, we briefly encounter the muses associated with arithmetic and geometry in the opening scene of Histrio-Mastix. The character Peace addresses the seven liberal arts and sciences, briefly introducing Arithmetick and Geometrie. These characters only appear in the beginning of the play, where they present what they can do to help restore peace in society:

Ar[ithmetick]. Her graces in my numbers shall be seene, \\

So full that nothing can be added more, \\

Nor ought subtracted : true Arithmetick \\

Will multiply and make them infinite. \\

. . .

Geo[metrie]. And I will make her powers demonstratiue, \\

In all my angles, circles, cubes, or squares, \\

The very state of Peace shall seeme to shine, \\

In euery figure or dimensiue lyne [Marston 1610, Act I, Scene i].[4]

This characterisation of Arithmetick is much more connected with abstract concepts of infinitude and completeness than with mercantile utility. Similarly, Geometrie is associated with proof and certain knowledge rather than geography or measurement. If we compare the ways in which Marston described the muses to, for instance, how they were presented in Howell’s 1654 play The Nuptialls of Peleus and Thetis, the character Geometry is described in the following way:

I trace the earth all over by account, \\

as farre as Pindus or Parnassus Mount; \\

I Corinth view, where every one \\

Cannot arrive, 'tis I alone \\

Who can by Land-skips, Mapps, and Instruments, \\

Measure all Regions, and their vast extents [Howell 1654, Act III, Scene iii].

Similarly, Arithmetick is introduced as:

My youthfull charms make many hearts \\

With grones, and sighs, and sobs to smart \\

Beyond computing, yet could I \\

To number them my selfe apply, \\

But that thereof I make a smal account, \\

They to so many Cyphers do amount [Howell 1654, Act III, Scene iii].

These examples show how practical aspects were also associated with the muses. In the case of Geometry, the importance of geography and navigation as derivative sciences was highlighted by the attributes of maps and instruments. For Arithmetick, accounting and calculation were the main foci, illustrated by the attributes of numbers. Such emphasis on mercantile applications resonated with other visual representations of the period, which frequently centred around commerce and war as the main uses of the mathematical sciences. Yet, when compared to, e.g., frontispieces in textbooks that drew on learned traditions, the versions of the muses in plays such as Nuptialls appear to have been aimed at a more popular audience. On the other hand, navigational instruments and even Hindu-Arabic numerals were not widely understood or universally used in the Early Modern period. Nonetheless, they must have been recognisable enough for the play to successfully tap into popular perceptions. In contrast, although Marston’s Arithmetick and Geometrie characters evoked muse-like characterisations, they showed a different, more academic, and less stereotypical view of the mathematician himself, as we will see when we analyse the role of Chrisoganus.

[4] The written English language was still centuries from being standardised during the Elizabethan era in which playwrights such as Shakespeare and Marston were writing. Thus, the words “seene” and “seeme” are Elizabethan spellings of “seen” and “seem.” Moreover, the letters U and V had not quite yet been separated one from the other, so “demonstratiue” and “euery” would today be spelled “demonstrative” and “every.” The final line of this passage would read “In every figure or dimension lying.” (Note also that the double slashes (“\\”) are an editorial intervention to indicate line breaks in the original printed script.)

Laura Søvsø Thomasen (Royal Danish Library) and Henrik Kragh Sørensen (University of Copenhagen), "“A Magazine of all perfection”: Mathematics in the Early Modern Satire [i]Histrio-Mastix[/i] – The Mathematical Muses," Convergence (December 2024)