- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

The Life of Sir Charles Scarburgh: English Civil War and Medical Training

While Scarburgh was completing his work in pursuit of a medical degree, the English Civil Wars broke out. Despite his many academic accomplishments, Scarburgh lost his fellowship at Cambridge in 1643 due to his unshakable support of the royalist side of the conflict, and he was forced to relocate to Merton College at Oxford University [Jay 1899, 178].

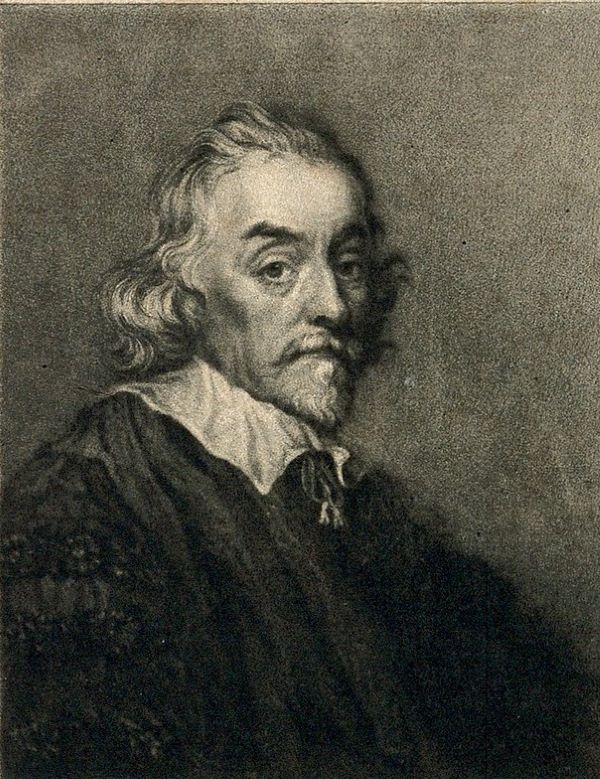

Figure 4. Mezzotint of William Harvey. Wellcome Library no. 4040i, made available by

Wellcome Collection via Creative Commons license 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

At Merton, he was able to study under another Caius graduate—and physician to King Charles I—William Harvey (1578–1657), known for his complete description of the circulatory system. Scarburgh studied at Merton for three years and, with Harvey’s recommendation, was awarded his medical degree on June 23, 1646 [Munk 1878, 252–253]. (Cambridge did eventually relent following the restoration of the monarchy and awarded Scarburgh his medical doctorate in 1660.)

Figure 5. Scarburgh and Dr. Edward Arris conducting an anatomical dissection.

Watercolour painting by G. P. Harding (1818) after an oil painting by R. Greenbury.

Wellcome Library no. 543625i, made available by Wellcome Collection

via Creative Commons license 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

After the surrender of Oxford to antiroyalist forces in the ongoing war, Harvey moved to London; Scarburgh eventually joined him there. In London, Scarburgh was elected to the College of Physicians in 1648 (and became a fellow in 1650), and he joined the Company of Barber-Surgeons in 1649 [Keevil 1952, 115]. The watercolor in Figure 5 above shows Scarburgh (on the left) as well as Edward Arris (d. 1676), who in 1645 endowed the Barber-Surgeons to pay for an annual public dissection of a human body followed by six public lectures [Ellis 1979, 71].

According to a contemporary source, the public lectures presented by Scarburgh contained mathematics as well as anatomy. In The Royal College of Physicians, published in 1684, Charles Goodall stated, “Sir Charles Scarburgh . . . was the first who introduced Geometrical and Mechanical Speculations into Anatomy, and applied them as well in all his learned conversation, as more particularly in his famous Lectures upon the Muscles of Humane Bodies for 16 or 17 years together in the publick Theatre at Surgeons-Hall, which were Read by him with infinite applause and admiration of all sorts of learned persons about the Town, who resorted in great numbers to those Readings” [Goodall 1684, 358]. Unfortunately, no actual texts of these lectures supposedly infused with mathematics have survived to the present day. Scarburgh did eventually publish a short work on muscular anatomy in 1676, Syllabus Musculorum, but it contains no mathematics at all.

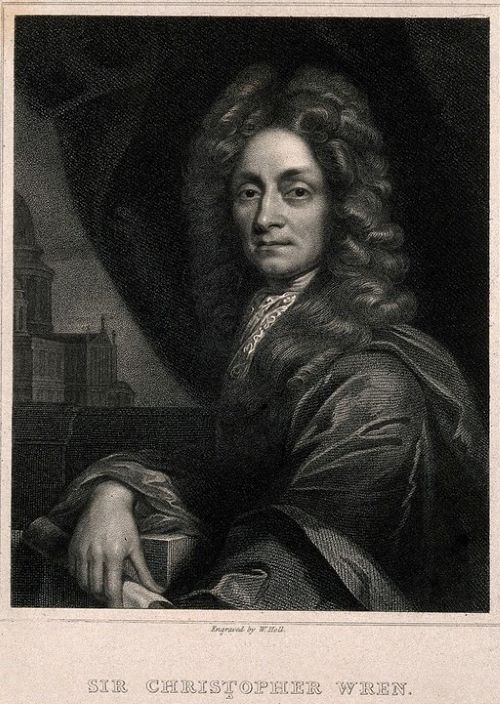

Figure 6. Sir Christopher Wren. Stipple engraving by W. Holl after Sir G. Kneller.

Wellcome Library no. 10057i, made available by Wellcome Collection

via Creative Commons license 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

During the years from 1646 to 1649, Scarburgh had as his teenaged assistant Christopher Wren (1632–1723), who would go on to become a renowned mathematician and architect, and who would eventually replace Seth Ward as the Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford in 1661 [Bennett 2002, 24]. Wren constructed working pasteboard models of the movement of muscles that Scarburgh could use to demonstrate in his public lectures; sadly, all of the models were destroyed in the London fire of 1666 [Keevil 1952, 115–116]. The two also worked in mathematics, and in a letter to Oughtred in 1647, Wren stated that he owed to Scarburgh “any little skill that I can boast in Mathematics” [Milman 1908, 21].

Scarburgh and his old friend Seth Ward also began to participate in a number of meetings with other scientifically-minded individuals in London, such as Robert Boyle [Milman 1908, 23–24]. These meetings eventually led to the 1660 creation of the Royal Society, of which Scarburgh would be one of the original fellows [Munk 1878, 253].

Michael Molinsky (University of Maine at Farmington), "The Life of Sir Charles Scarburgh: English Civil War and Medical Training," Convergence (June 2021)