- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

Quotations in Context: Thoreau

“He is not a true man of science who does not bring some sympathy to his studies, and expect to learn something by behavior as well as by application. It is childish to rest in the discovery of mere coincidences, or of partial and extraneous laws. The study of geometry is a petty and idle exercise of the mind, if it is applied to no larger system than the starry one. Mathematics should be mixed not only with physics but with ethics, that is mixed mathematics. The fact which interests us most is the life of the naturalist. The purest science is still biographical.”

Naturalist Henry David Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers at his own expense in 1849. The book related events from a trip taken a decade earlier by Thoreau and his brother John through Massachusetts and New Hampshire, combined with selections of poetry and Thoreau’s views on a wide range of topics. Although the actual trip lasted two weeks, the book itself is organized around a single week, starting with the last Saturday in August 1839 and proceeding through the following Friday.

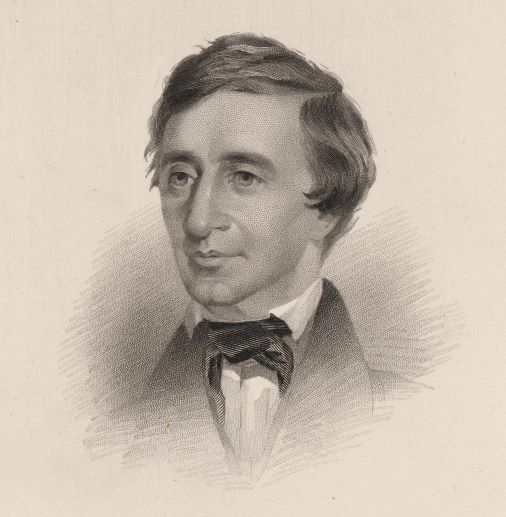

Engraving of Thoreau by unknown artist, based on work of Samuel Rowse. Public domain, National Portrait Gallery.

It was on this last day, Friday, when Thoreau’s thoughts turned to mathematics. On the previous Sunday, Thoreau and his brother had encountered a “lover of the higher mathematics” [Thoreau 1849, p. 84] who was called away from consideration of an unspecified mathematical problem in order to let their boat through the locks onto the Merrimack, and on Friday they met the same individual again on their return trip. This meeting apparently inspired Thoreau to consider mathematics and science, and particularly their relation to truth and beauty, as he stated that appreciation of the beauty of scientific truth is much rarer than the appreciation of moral truth. He then switched specifically to mathematics:

We have heard much about the poetry of mathematics, but very little of it has yet been sung. The ancients had a juster notion of their poetic value than we. The most distinct and beautiful statement of any truth must take at last the mathematical form. We might so simplify the rules of moral philosophy, as well as of arithmetic, that one formula would express them both [Thoreau 1849, p. 381].

Thoreau extended this claim, emphasizing the connection between moral laws and natural philosophy, and he argued for strong interaction and connection between scientific and ethical truth. It was at this point in the book that the quotation at the beginning of this column appears [Thoreau 1849, pp. 381–382].

In the following paragraphs, Thoreau explored additional topics, such as the process of scientific discovery and the particular need for genius, arguing that “the power to perceive a law is equally rare in all the ages of the world” [Thoreau 1849, p. 384]. Before returning to the description of the final stages of his journey down to Concord, Thoreau briefly related an account of the voyage of Sir James Clark Ross to Antarctica, including the fact that the crews were given additional rations of grog as a reward for reaching further south than any before. Thoreau concluded by using this story to return to his point about the importance of genius over the mere collection of facts:

Let not us sailors of late centuries take upon ourselves any airs on account of our Newtons and our Cuviers; we deserve an extra allowance of grog only [Thoreau 1849, p. 385].

Reference

Thoreau, Henry David. 1849. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Boston: James Munroe and Company.

“Quotations in Context” is a regular column written by Michael Molinsky that has appeared in the CSHPM/SCHPM Bulletin of the Canadian Society for History and Philosophy of Mathematics since 2006 (this installment was first published in May 2016). In the modern world, quotations by mathematicians or about mathematics frequently appear in works written for a general audience, but often these quotations are provided without listing a primary source or providing any information about the surrounding context in which the quotation appeared. These columns provide interesting information on selected statements related to mathematics, but more importantly, the columns highlight the fact that students today can do the same legwork, using online databases of original sources to track down and examine quotations in their original context.

Michael Molinsky (University of Maine at Farmington), "Quotations in Context: Thoreau," Convergence (May 2024)