- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

Mathematical Treasure: Adelard’s Translation of Euclid’s Elements

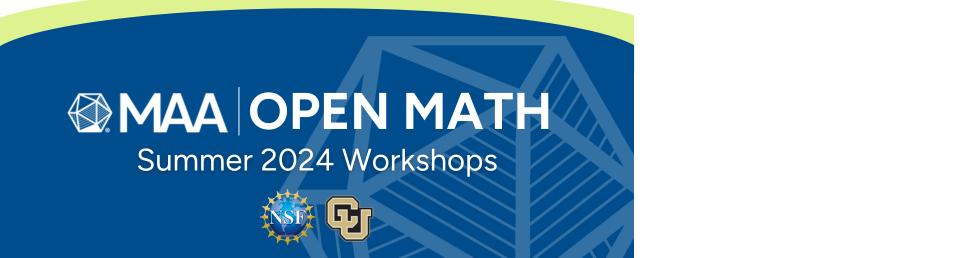

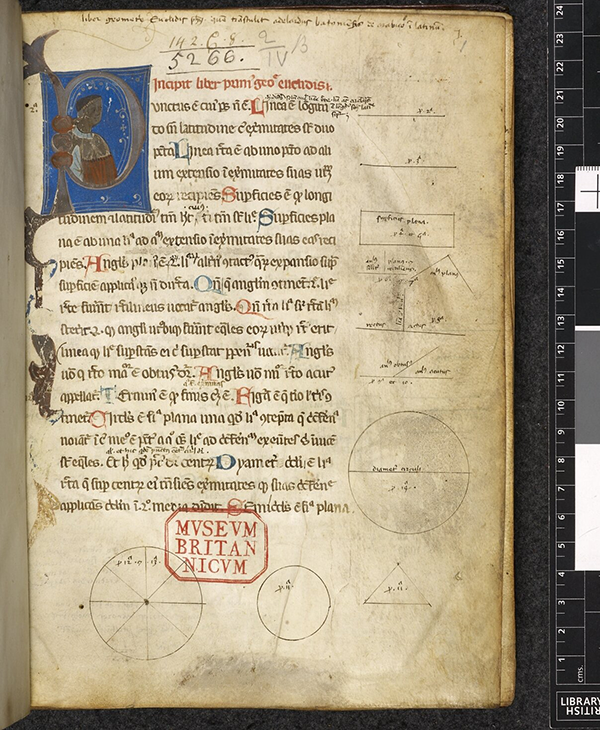

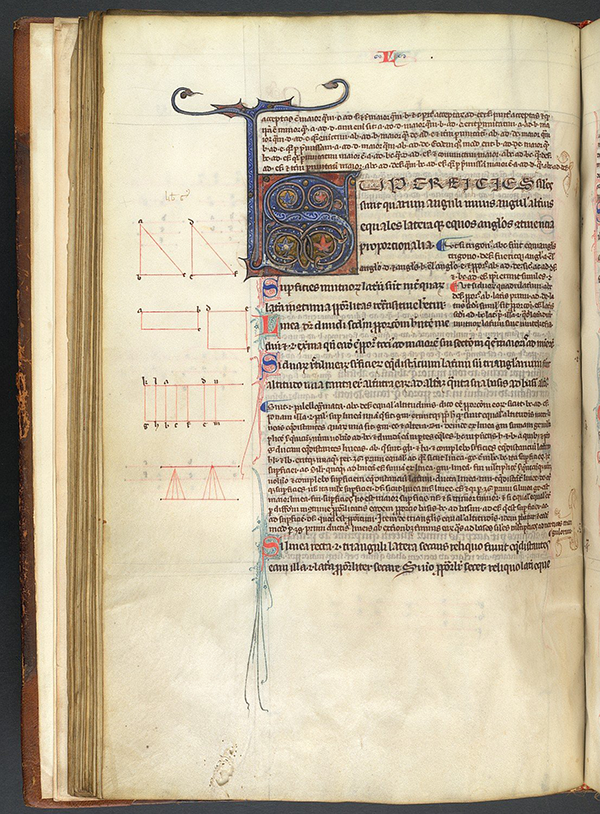

Shown below is an early 14th century manuscript (Harley MS 5266) containing a translation of Euclid’s Elements by Adelard of Bath (ca. 1075 – ca. 1160). Adelard, a British scholar, was the first person known to have translated the Elements from Arabic into Latin. The text begins on folio 1r, highlighted by an illumination depicting Euclid:

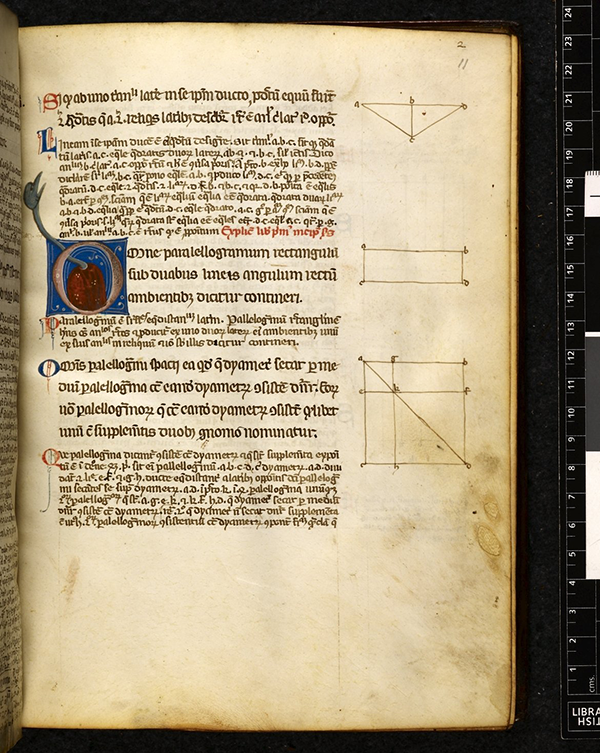

Folio 11r from the same 14th century manuscript discusses the properties of various geometric figures:

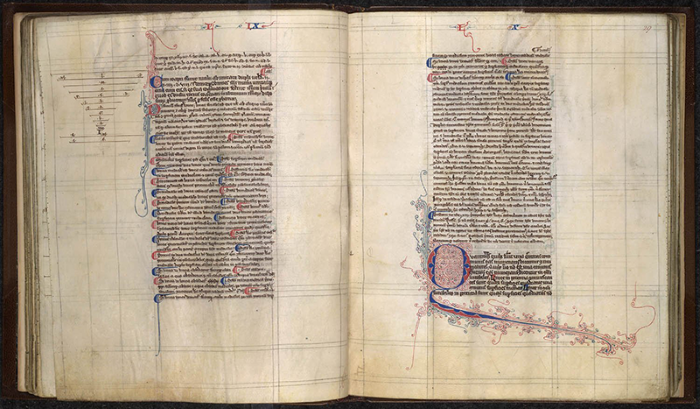

An elegantly illustrated 13th century French manuscript (Sloane MS 285) of Adelard’s translation, Elementa geometriae, appears below. The pages are numbered IX and X (folios 28-29):

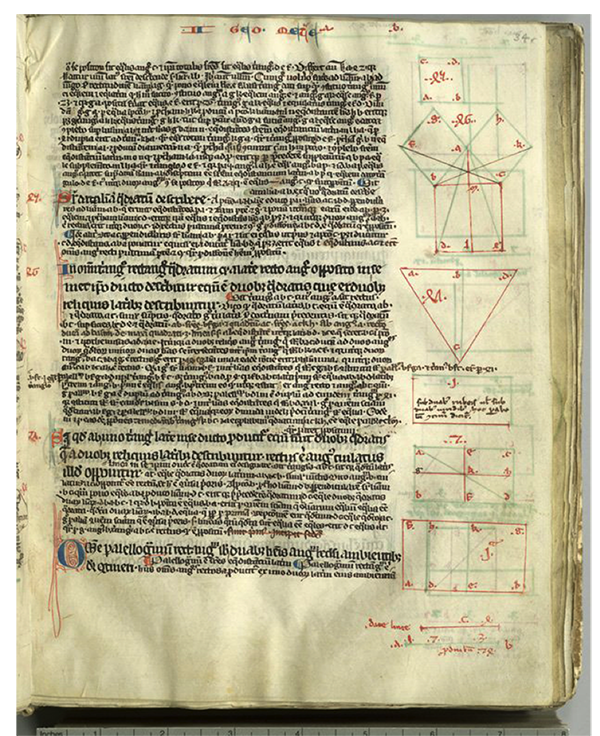

This is an excerpt from another 13th century French manuscript (Arundel MS 84) of Adelard of Bath’s translation of Euclid’s Elements. It is on folio 33v of the manuscript:

Folio 34r of this same 13th century manuscript contains diagrams that should be familiar to any student who has studied Euclidean geometry:

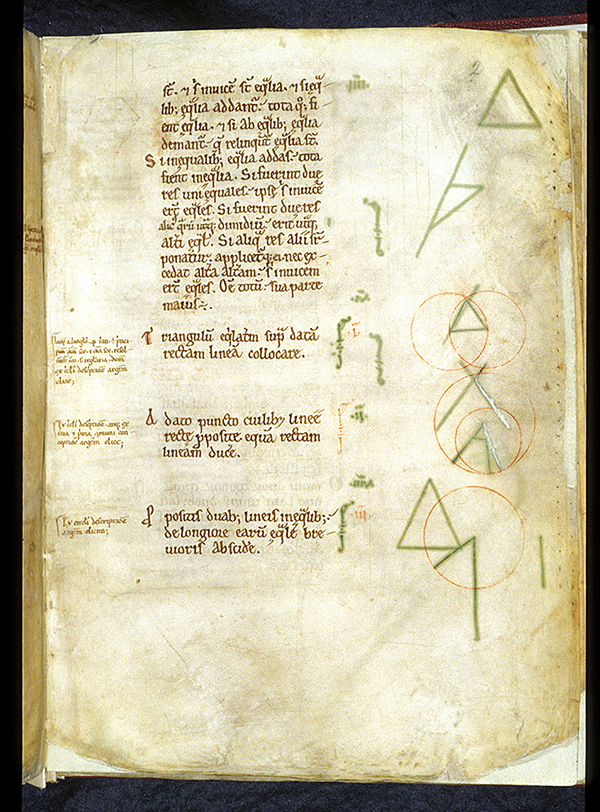

An English manuscript from the 12th century (Royal MS 15AXXVII) contains Adelard’s Euclid. Folio 2 contains definitions; however, the construction of marginal illustrations posed some difficulty:

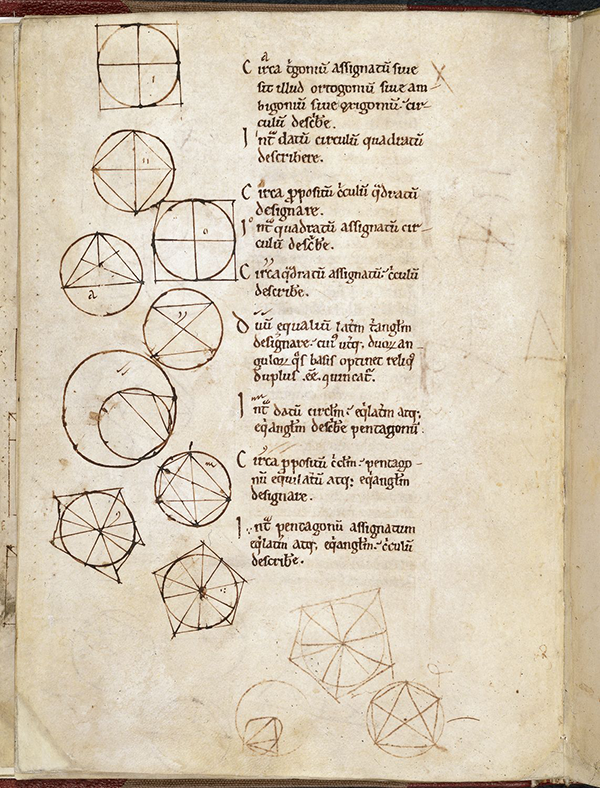

On folio 11v of the 12th century manuscript, properties of inscribed and circumscribed circles are discussed and illustrated:

Another copy of Adelard's version of Elements is found within a collection of 21 treatises (Burney MS 275, folios 293r–335r) on various subjects within the medieval quadrivium and trivium that dates to 1309–1316. Of particular interest is the illumination in the top left corner of the first page of the manuscript. A woman, the Muse of Geometry, instructs a group of stonemasons. In her left hand she holds a stonemason’s set square, and in her right hand she employs a stone grapple, officially known as a Lewis, to choose stone-cut ornamentations from the table before her. Such personalization of Geometry as one of the liberal arts was first conceived by Martianus Capella in his 5th-century work, De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii. In the Middle Ages, an illustration that shows a woman instructing men, especially stonemasons, members of a proud and powerful guild, would have been highly unusual. However, this picture testifies to the important and strong relationship of geometry with architecture at this period of history. This drawing, like the others in this manuscript, has been attributed to the Méliacin Master, who worked in Paris around 1280–1310.

The images above were obtained through the courtesy of the British Library. Further investigation of the images and their source can be obtained through the online services of the British Library. Where possible, manuscript reference numbers are given for the item being viewed.

Frank J. Swetz (The Pennsylvania State University), "Mathematical Treasure: Adelard’s Translation of Euclid’s Elements," Convergence (August 2019)