- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

'The Ladies Diary': A True Mathematical Treasure - Conception and Evolution

Figure 2. Black and white copy of the cover of the 1787 edition of the Ladies' Diary or Woman’s Almanack, which bears a portrait of Charlotte, who reigned as Queen Consort of King George III from 1761 until her death in 1818. (Source: Internet Archive, from a book held by Oxford University Library and digitized by Google.)

By the beginning of the 18th century, England had asserted herself as a major international power. Her navy ruled the seas and her colonies, particularly those in North America, provided a lucrative trade network. The Industrial Revolution was just starting to take hold and the nation was experiencing a period of relative peace. Spawned by such advantageous conditions, a rising middle class of “Ladies and Gentlemen” was affecting English daily life. Usually offspring of financially and/or professionally successful parents, they disdained physical work and embraced fashion, pleasant manners and, most of all, leisure. A Gentleman would most likely attend a Public School where he would be exposed to Latin and Greek and be prepared for entering a university, preferably Oxford or Cambridge, or a profession of approved status. In contrast, Ladies, preordained as wives, would most likely be trained at home, learning domestic skills and appropriate behavior. A few might attend a private Ladies' Academy where they would be exposed to a limited set of higher arts contributing to polite behavior, such as music, singing and poetry.

Both sexes of the rising middle class, along with many who aspired to it, enjoyed reading both as a pastime and as a means for acquiring new knowledge of their rapidly changing world. To meet this need, publishers supplied a large and varied source of materials: newspapers, broadsheets, periodicals, and books. Principal among this collection of print material were almanacs (Capp, 1979). Such modest books, usually just a few pages in length, were very popular for their chronological referencing, supplying an augmented calendar noting official holidays, church feast days, and days of advised action, such as when to harvest or plant a crop or undertake a journey. Unfortunately, this predictive capacity most often involved astrology, a practice adhered to by many English common folk. Some almanac editors attempted to extend their scope of information, and the attractiveness of their publications, by including political diatribes and tantalizing anecdotes and gossip.

One such enterprising editor was John Tipper (1663-1713), a Coventry schoolmaster and sometime textbook author. Mindful of the growing leisure class of young women and their intellectual restlessness, he conceived of an almanac just for women, the Ladies Diary or Woman's Almanack. At this time there were no specific periodicals or magazines for women. In the latter part of the seventeenth century, a publisher, John Dutton, had attempted two journals designed for women, but his content demeaned and preached to its female readers. These journals failed quickly. Tipper believed he could cater successfully to the “Fair Sex” by supplying “genteel” subject matter, such as household tips, recipes, health advice, poems, and “delightful” romantic stories, along with the standard calendar and chronological reckonings of an almanac. His program was devised without any female input, not even that of his own wife.

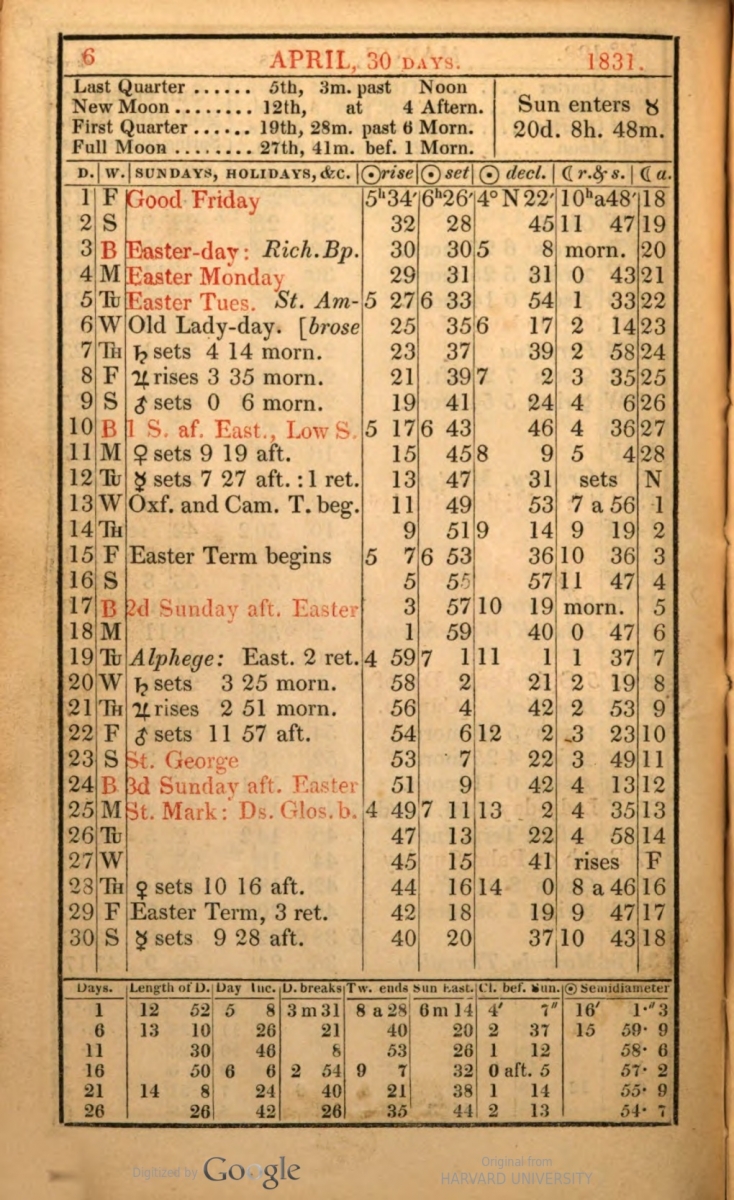

Figure 3. A typical almanac calendar page, this one for the month of April, 1831, from the 1831 Ladies Diary. Pages like this one, featuring meaning and ordering of numerals, comprised about one third of the Ladies Diary. Such pages became familiar to readers and helped advance numeracy. (Source: HathiTrust Digital Archive, from a book held by Harvard University Library and digitized by Google)

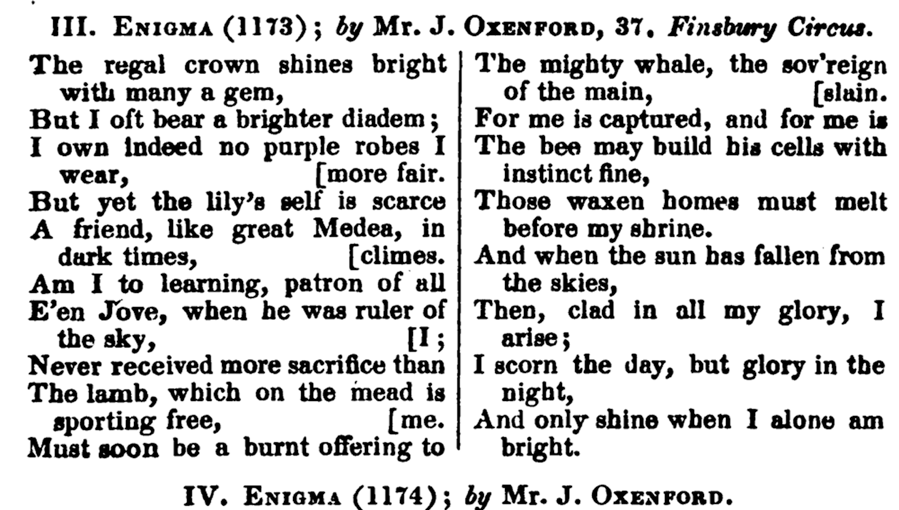

One prominent feature of Tipper's Ladies Diary was the inclusion of "enigmas," or word puzzles, a pastime that was all the rage among English women at the time. This practice had been adopted from France, where fashionable ladies asserted themselves by demonstrating their wit and knowledge through posing and solving such riddles. Tipper encouraged interaction and correspondence, both with himself and between his readers, and much of it was about these puzzles.

Figure 4. A typical "enigma" puzzle from the Ladies Diary of 1835 (p. 27). The answer is "a candle."

At this time, the publishing of all almanacs in England was controlled by the London-based Worshipful Company of Stationers, a monopoly instituted by royal decree (Feist, 2005). Thus, John Tipper had to secure this organization's compliance in publishing and marketing his proposed periodical. The Company reluctantly agreed, but limited the first release to just three thousand issues and demanded a higher-than-market sales price for the almanac. Despite such misgivings and limitations, the Ladies Diary was a great success from its first issue in 1704, and remained so for the next century and a half, becoming one of the longest continuously running periodicals in the history of Great Britain.

"'The Ladies Diary': A True Mathematical Treasure - Conception and Evolution," Convergence (August 2018)