- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

Apportioning Representatives in the United States Congress - The Quota Rule

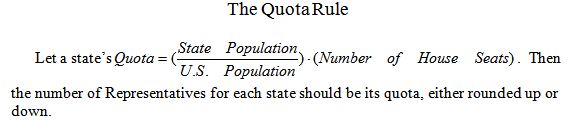

The fact that the affected states in the discrepancy just mentioned are Virginia and Delaware is no coincidence. In general, Jefferson’s method is biased in favor of larger states and against smaller ones. It violates what is called the “Quota Rule:

Here is a table that compares the populations and Representatives of Virginia and Delaware from 1790 through 1840:

|

Year |

VA Pop. |

Quota |

Rep’s |

DE Pop. |

Quota |

Rep’s |

|

1790 |

630,560 |

18.31036 |

19 |

55,540 |

1.61278 |

1 |

|

1800 |

747,362 |

21.55048 |

22 |

61,812 |

1.78237 |

1 |

|

1810 |

817,615 |

22.47609 |

23 |

71,004 |

1.95188 |

2 |

|

1820 |

895,303 |

21.25999 |

22 |

70,943 |

1.68462 |

1 |

|

1830 |

1,023,503 |

20.58844 |

21 |

75,432 |

1.51736 |

1 |

|

1840 |

1,060,202 |

14.86167 |

15 |

77,043 |

1.07997 |

1 |

|

|

Totals |

119.04703 |

122 |

|

9.62898 |

7 |

By 1810, New York had overtaken Virginia as the most populous state in the Union. If we look at its numbers instead of Virginia’s, the discrepancy between that large state and Delaware is even more pronounced:

|

Year |

NY Pop. |

Quota |

Rep’s |

DE Pop. |

Quota |

Rep’s |

|

1790 |

331,589 |

9.628765 |

10 |

55,540 |

1.61278 |

1 |

|

1800 |

577,805 |

16.66124 |

17 |

61,812 |

1.78237 |

1 |

|

1810 |

953,043 |

26.19898 |

27 |

71,004 |

1.95188 |

2 |

|

1820 |

1,368,775 |

32.50313 |

34 |

70,943 |

1.68462 |

1 |

|

1830 |

1,918,578 |

38.59347 |

40 |

75,432 |

1.51736 |

1 |

|

1840 |

2,428,919 |

34.04803 |

35 |

77,043 |

1.07997 |

1 |

|

|

Totals |

157.6336 |

163 |

|

9.62898 |

7 |

Using Jefferson’s method, New York always had its quota rounded up. On two occasions, its quota was rounded up more than one whole unit, in violation of the Quota Rule. In contrast, Delaware’s quota was rounded up only once. More striking are the cumulative results, showing New York well above and Delaware well below their expected totals.

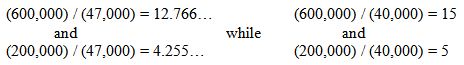

There is a simple explanation for Jefferson’s bias toward the large states. The method works by lowering the divisor D by some d until the rounding fits the specified number of seats. But lowering the divisor causes the quotient to grow at a faster rate if the dividend is higher. For example,

Lowering the divisor by 7,000 in each case raises the quotient by more than 2.2 in the case of the large dividend but only by 0.75 in the case of the small one.

Michael J. Caulfield (Gannon University), "Apportioning Representatives in the United States Congress - The Quota Rule," Convergence (November 2010), DOI:10.4169/loci003163